CNN

By John Blake, CNN

March 5, 2021 The vast Fairgrounds Park pool in St. Louis, in an undated photo. It closed in 1956.

The vast Fairgrounds Park pool in St. Louis, in an undated photo. It closed in 1956.

If you’re a White person who thinks racism only hurts people of color, the story behind an empty, abandoned swimming pool in Missouri might just change your mind.

The Fairground Park pool in St. Louis was the largest public pool in the US when it was built in 1919. It featured sand from a beach, a fancy diving board and enough room for up to 10,000 swimmers. It was dug during a pool-building boom when cities and towns competed to provide their citizens with public amenities that promoted civic pride and symbolized a perk of the American dream.

These public pools, of course, were for Whites only. But when civil rights leaders successfully pushed for them to be integrated, many cities either sold the pools to private entities or, in the case of Fairground Park, eventually drained them and closed them down for good.

These closures didn’t just hurt Black people, though — they also denied the pleasures of the pool to White people.

Heather McGhee tells the story of the Fairground Park pool in her powerful new book, “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together.” McGhee employs the metaphor of a drained, cracked public pool to make a larger point: White refusal to share resources available to all US citizens doesn’t just hurt people of color. It damages their families and their future, too.

McGhee has a name for this pain. She calls it “drained-pool politics.” If you want to know why the US has one of the most inefficient health care systems among advanced nations, some of the worst infrastructure and a dysfunctional political system, blame drained-pool politics, she says.

Those politics are built on a lie that many White Americans have bought for centuries: When Black or brown people gain something, White people lose.

“The narrative that White people should see the well-being of people of color as a threat to their own is one of the most powerful subterranean stories in America,” McGhee writes in her book. “Until we destroy the idea, opponents of progress can always unearth it, and use it to block any collective action that benefits us all.” Heather McGhee

Heather McGhee

McGhee’s book debuted last week at #3 on The New York Times’ nonfiction bestseller list and is already so popular that her publisher is scrambling to keep up with demand. It comes less than a year after the George Floyd protests sparked a national racial reckoning.

But McGhee’s book doesn’t just make the familiar “White people are voting against their economic interests” argument that many of us have heard before. She fills it with personal stories from her life and the people she encountered during three years of visiting churches, union halls and small towns across America.

McGhee’s book may soon be regarded as a classic in race literature and the phrase “drained-pool politics” could join “White fragility” in the lexicon people invoke when talking about race.

McGhee, a former president of Demos, a progressive think tank, recently spoke to CNN about her new book and this moment in America’s racial history. Our conversation was edited for clarity and length.

How would you explain to, say, a White Trump voter motivated by racial resentment that racism has harmed him? Supporters of President Donald Trump in Bristol, Pennsylvania, on October 24, 2020.When you think about “Make America Great Again,” that time period was a time when a White guy could walk into a factory and walk out set for life, when college was paid for the government, when a great middle-class house was subsidized by the government, when the minimum wage was high and when taxes were high.That formula is a formula that you reject now when given the political choice between a strong middle class and the party that markets to your race but delivers economic benefits only to the wealthy.

Supporters of President Donald Trump in Bristol, Pennsylvania, on October 24, 2020.When you think about “Make America Great Again,” that time period was a time when a White guy could walk into a factory and walk out set for life, when college was paid for the government, when a great middle-class house was subsidized by the government, when the minimum wage was high and when taxes were high.That formula is a formula that you reject now when given the political choice between a strong middle class and the party that markets to your race but delivers economic benefits only to the wealthy.

You cite the 2008 housing market crash as a “fire” that started in Black and brown communities but eventually spread to White communities as well. Can you cite another example of something that was seen as a problem largely confined to Black people that ended up costing White people, too?The pandemic itself is an example of a virus that hit the Black and Brown and indigenous communities first and worse. And then the illusion that it was only happening to blue cities and brown people allowed the Trump administration to take its eye off the ball and downplay the risks and turn it into a culture war, an “us vs. them” where Covid support shouldn’t go to blue states, which was also signifying brown people.That is an example of the fires raging in Black, brown and indigenous communities that were disproportionately exposed because of systemic racism. And then nine months later the highest rates are in (heavily White) places like South and North Dakota and West Virginia and then you realize that our fates are linked.

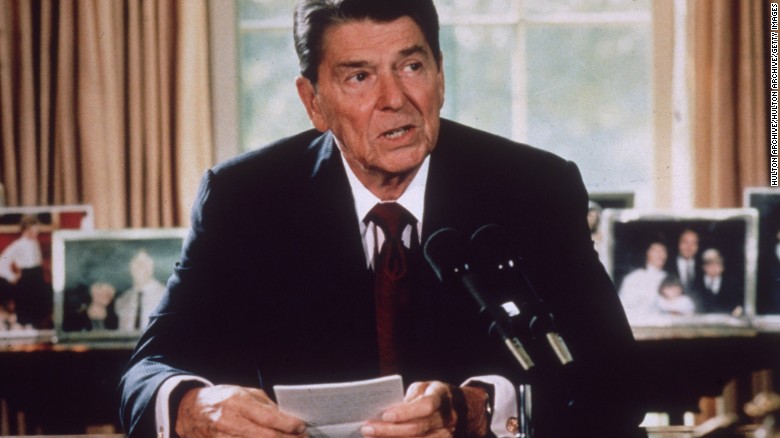

As you explain, White support for government programs that built up the White middle class actually fell as the civil rights movement blossomed because of a zero-sum approach to politics — whatever helps Black people must hurt Whites. When President Reagan said in his first inaugural address that government was the problem, was he invoking the zero-sum perspective that you talk about? President Ronald Reagan famously said in 1981: “government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem.”He was. What had government done wrong? When you think about the picture that Ronald Reagan was trying to paint of government mismanagement and government’s poor judgment, you’d already had a decade of the War on Poverty, which was an extension of public benefits across the color line — from it being up until the 1960s largely for White people.And so there was an image in the White American mind of what business government had gotten into, that they shouldn’t have been in it and that they didn’t do well. There was a racialized story and the term “public” had already become degraded and associated with people of color: public housing, and public schools that had already become integrated.You think about the ways in which government provided for the common good during the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s and in ways that built the White middle class. My book includes a section where it lists all the free stuff that the government gave to White families to help them have intergenerational wealth and economic security and how once we began to desegregate, government became stingier and that impacted everybody.

President Ronald Reagan famously said in 1981: “government is not the solution to our problem, government IS the problem.”He was. What had government done wrong? When you think about the picture that Ronald Reagan was trying to paint of government mismanagement and government’s poor judgment, you’d already had a decade of the War on Poverty, which was an extension of public benefits across the color line — from it being up until the 1960s largely for White people.And so there was an image in the White American mind of what business government had gotten into, that they shouldn’t have been in it and that they didn’t do well. There was a racialized story and the term “public” had already become degraded and associated with people of color: public housing, and public schools that had already become integrated.You think about the ways in which government provided for the common good during the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s and in ways that built the White middle class. My book includes a section where it lists all the free stuff that the government gave to White families to help them have intergenerational wealth and economic security and how once we began to desegregate, government became stingier and that impacted everybody.

You said in the book that “refilling the pool requires us to believe in government again.” How important then is the pending Covid relief bill and a new voting rights bill just passed by the House in getting people to believe in government again?There are some success stories in the country’s pandemic response and in places where the vaccine is being delivered well. Here in New York, for example, I got my first vaccine shot and it was Air Force personnel who were delivering the shots and it was FEMA that had set up the site and it was on the grounds of a public community college. That is a beautiful thing, seeing our government do its job to help people who absolutely couldn’t help themselves.And that’s the kind of sight to we need to see more of so that we can restore our faith in the possibility of what we can do together. The exact counter to that is in Texas, a state cut off from the federal government to avoid being regulated, to avoid the kinds of safeguards that would have stopped the power outages, a state government that was totally absent from prevention to mitigation and taking care of its people. That was a very clear example of drained pool politics, of anti-government sentiment being put into policies that hurt everyone. It cost lives.

You praise the Fight for $15 campaign to raise the minimum wage. What did that campaign do right to avoid zero-sum politics, to avoid people using race to divide White and Black and brown workers? Protesters attend a rally for a $15 hourly minimum wage on February 16, 2021, in Orlando, Florida.They talked about it. They explicitly made the idea of racism as a divide-and-conquer tool a part of worker education, a part of the rhetoric, a part of the protest signs. The zero sum is so pervasive in our politics and is part of the right-wing messaging that in order to counter it you have to engage with it head on, you have to call it out. Give people a way to recognize it and reject it.

Protesters attend a rally for a $15 hourly minimum wage on February 16, 2021, in Orlando, Florida.They talked about it. They explicitly made the idea of racism as a divide-and-conquer tool a part of worker education, a part of the rhetoric, a part of the protest signs. The zero sum is so pervasive in our politics and is part of the right-wing messaging that in order to counter it you have to engage with it head on, you have to call it out. Give people a way to recognize it and reject it.

I’ve heard many political scientists say, though, that the way you sell a policy that helps Black or brown people is to make it race-neutral. They say, for example, when Obamacare was seen as something pushed for by a Black president for people of color, it wasn’t popular. But now that it’s seen as a program that benefits White people, it’s more popular.Let’s be very clear. Obama didn’t talk about it in terms of race. This is the point. Policies — you can’t avoid race. Race is the central character in the drama about government and our economy. If you don’t acknowledge that and give voters another way of thinking about race, then you’re just missing a huge part of the story.

You write that diversity is the country’s “superpower.” What do you mean? Demonstrators protest on May 31, 2020, in St. Paul, Minnesota, after the death of George Floyd.The research shows that diversity allows groups to think better about critical problems. It is the friction of coming from different backgrounds and looking at issues from different vantage points that creates a productive energy, and we are one of the most diverse nations. There is someone here with a tie to every community on the globe and we could use that to our competitive advantage and yet the “us vs them,” zero-sum quality that we have is holding back our potential.

Demonstrators protest on May 31, 2020, in St. Paul, Minnesota, after the death of George Floyd.The research shows that diversity allows groups to think better about critical problems. It is the friction of coming from different backgrounds and looking at issues from different vantage points that creates a productive energy, and we are one of the most diverse nations. There is someone here with a tie to every community on the globe and we could use that to our competitive advantage and yet the “us vs them,” zero-sum quality that we have is holding back our potential.

Did writing this book and traveling across the US to meet people make you more optimistic or pessimistic about the country’s future?I left my travels much more optimistic because I saw these signs of the solitary dividends in nearly everywhere I visited, in pockets of America where people are crossing liens of race and unlocking that diversity superpower and rejecting the zero sum. That is really exciting to me.We’re at a moment of awakening in this country where more and more White folks are feeling that they have to relearn and unlearn some of what they’ve learned. And there’s a sense of wanting to change our course, recognizing that we have gone off course as a country and that we have to face up to decisions in order to really have the country we all deserve.