Getting Smart

By Rebecca Midles and Rashawn Caruthers July 15, 2021

Remember coming in after recess in elementary to a 20-question math quiz? If you were done first, you were smart. If it looked easy for you, you were also smart. Over the years, authentic assessment and personalized learning have started to change this idea of “smart”. When combined with Carol Dweck’s research on growth mindset, learners embrace growth, openness, and innovative ideas. How we provide feedback as educators and parents can send a message about not only how we see the learning, but the learner as well.

In order to create a learning culture that embraces growth mindset one must create a safe learning environment that honors all learners, experiences and cultures; teach learners the basics of learning science so they better understand conditions, context and thriving; and practice giving feedback in thoughtful ways.

Due to systemic inequities in the education system, traditionally underserved populations are more likely to have a fixed mindset. According to a recent Brookings Report, “Traditionally underserved students – including students in poverty, English learners, Hispanics, and African-American students – are less likely to hold a growth mindset.” Mindset, like intelligence, is not stagnant and learners can move from a fixed to growth mindset with the right support.

For students to thrive, or as Gholdy Muhammad would say, have their genius seen, both teachers and students have to constantly practice having a growth mindset. Some students may arrive knowing exactly who they are and what’s possible, while others will need more support to imagine a reality that changes their trajectory for the better. It is critical that teachers don’t under expect what students can do and, to address the harm caused by systemic racial inequities in education, educators need to believe that their historically underrepresented students can achieve the same rigorous content as their dominant-culture peers.

Building a growth mindset culture does not stop at awareness. Implementing the following strategies and tools for learners provides them access to feel empowered in their learning and to be able to impact their growth.

1. Trust, Nurture Relationships

Trust and relationships begin to develop when students are heard, and students–particularly those that have experienced personal and/or generational trauma–need trusting relationships to feel comfortable in a learning culture. While designing, consider how students will know that they’re being heard. This builds relationships and makes space for trust to be earned and praise to be received. Educators can use the “Four Elements of Trust” and be intentional in their approach. The Four Elements are consistency, compassion, competence, and communication.

Select or create mechanisms to capture student voice on a daily basis and foster collaboration. Consider how you will learn and gather insights to how students feel about themselves and how they learned or didn’t on a particular day. When students communicate that they don’t feel smart, that they struggled, or that they don’t feel as capable as their peers, intentional structures can be implemented or activated to change the mindset from fixed to growth. When learners are validated and affirmed, they are more likely to feel seen, valued for their contributions, and ready to learn. When learner ideas are at the center of instruction, teachers signal that they respect and value students’ thinking.

2. The Brain and How Learning Works

Learners need to learn about the brain and how it works. This can include a phased approach to teaching the science, but the most important part is explicitly teaching that the brain is not fixed at birth and that it changes and grows (this idea is often referred to as neuroplasticity). Understanding how long-term learning happens and the role stress, anxiety and emotion play in this process helps learners better understand how their body works, their stages of development and how they can impact their own learning.

There are many resources to use and stories to share that support the effort of ‘rewiring’ your brain. The MindUP Curriculum provides K-8 resources for How Your Brain Works. (Example video for grades 3-5). For parent support in teaching about the brain, MindsetWorks refers to this work as Brainology and Growing Early Mindsets (GEM) and more can be found on their website.

3. Mindsets and Difference Between Growth and Fixed

Teaching the difference between a fixed mindset and a growth mindset is a common first step for people seeking to build a learning culture, but this phase will often reach more students more deeply when they first learn about the science of how we learn, as discussed in phase two above.

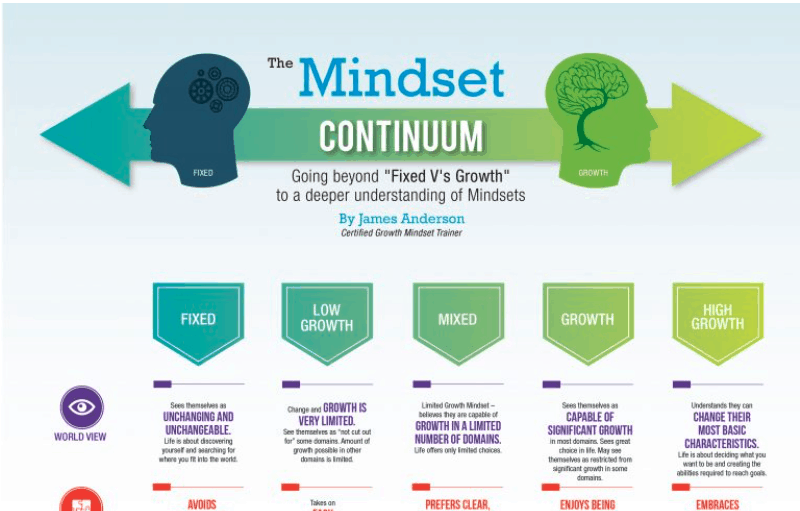

MindsetWorks provides many resources for teaching about mindsets. The Mindset Continuum chart identifies mixed mindsets and begins to show the progression and provides identifiers for growth. There are a number of common misconceptions about learning cultures, and it is worth getting familiar with a few of the many recent articles addressing them.

4. Feedback and the Power of Praise

Providing feedback, and especially praise, can shape a learner’s inner voice, as the feedback we give sets the tone for how we see learning and for how students see themselves as learners.

While some learners are instantly motivated by hearing what a good job they did, others may perceive it as being inauthentic because a relationship of trust hasn’t been established. When praise isn’t immediately welcomed, it can feel as though the student is being disrespectful or stubborn, but it could also simply be that the student doesn’t feel worthy of the praise because of low or vacant self-esteem. According to to Dr. Joy Degruy, “Individuals arrive at their self-esteem: first, as a result of the appraisals of the significant others in their lives; later, as a result of having their contributions appropriately recognized; and finally, as a result of the meaningfulness of their own lives.”

Praise must be implemented in three phases with the most important step being the first, relationship building. Learners, especially black and brown learners, are sometimes made to feel submissive which makes it difficult to receive and appreciate praise. Often when praise is given, especially in the larger societal context, it’s for skills unrelated to academics which continues to cement that praise for being “smart” is not for them and can’t be true.

If we praise the process when productive struggles have occurred, then we are saying this is learning and learning is not easy. In our opening example of math quizzes, what we choose to praise sends a message. Instead of noting when things were quick/easy we can call out productive struggles instead.

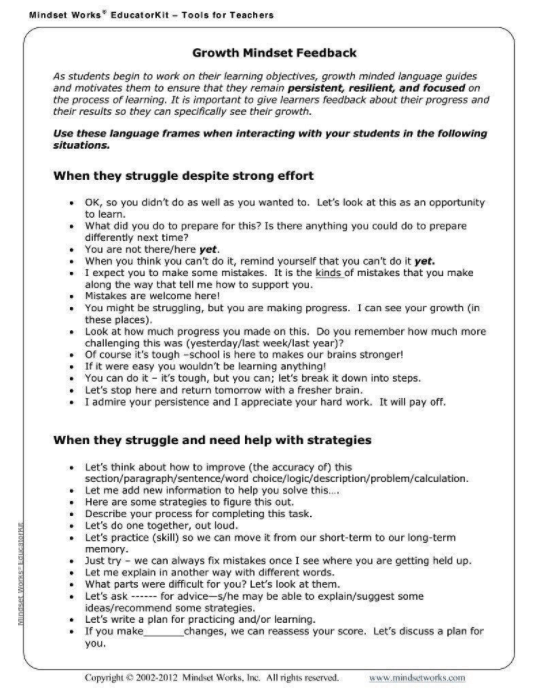

Teachers can practice adding to their repertoire of providing feedback and giving praise. One way to do this can be as simple as reviewing suggested sentence stems or praise like the ones provided by Mindset Works and reviewing them to help grow a feedback toolkit of phrases.

5. Using Your Inner Voice, Self-Talk

To change a mindset, learners need tools to reframe this voice and to build productive self-talk as they approach challenges. It is a good start to be aware of a fixed mindset or to even be aware of negative self-talk, but it is necessary to also provide strategies and tools to support growth. Teaching strategies facilitates all learners to believe in themselves and their ability to grow their intelligence.

A place to start is through mindful observations of your learners that are more like running records than a quick assumption. Kristine Mraz and Christine Hertz Hausman expand on this further in their book, A Mindset for Learning, with a chart of observable behaviors of learners and the examples of self-talk that may be occurring. They recommend noticing groups of learners that may not start right away, or get stuck or stalled. To observe which learners may only try once or perseverate on a small task. These observations will help prepare future discussions and conferring opportunities where learners reflect on a recent struggle and how they felt during that process.

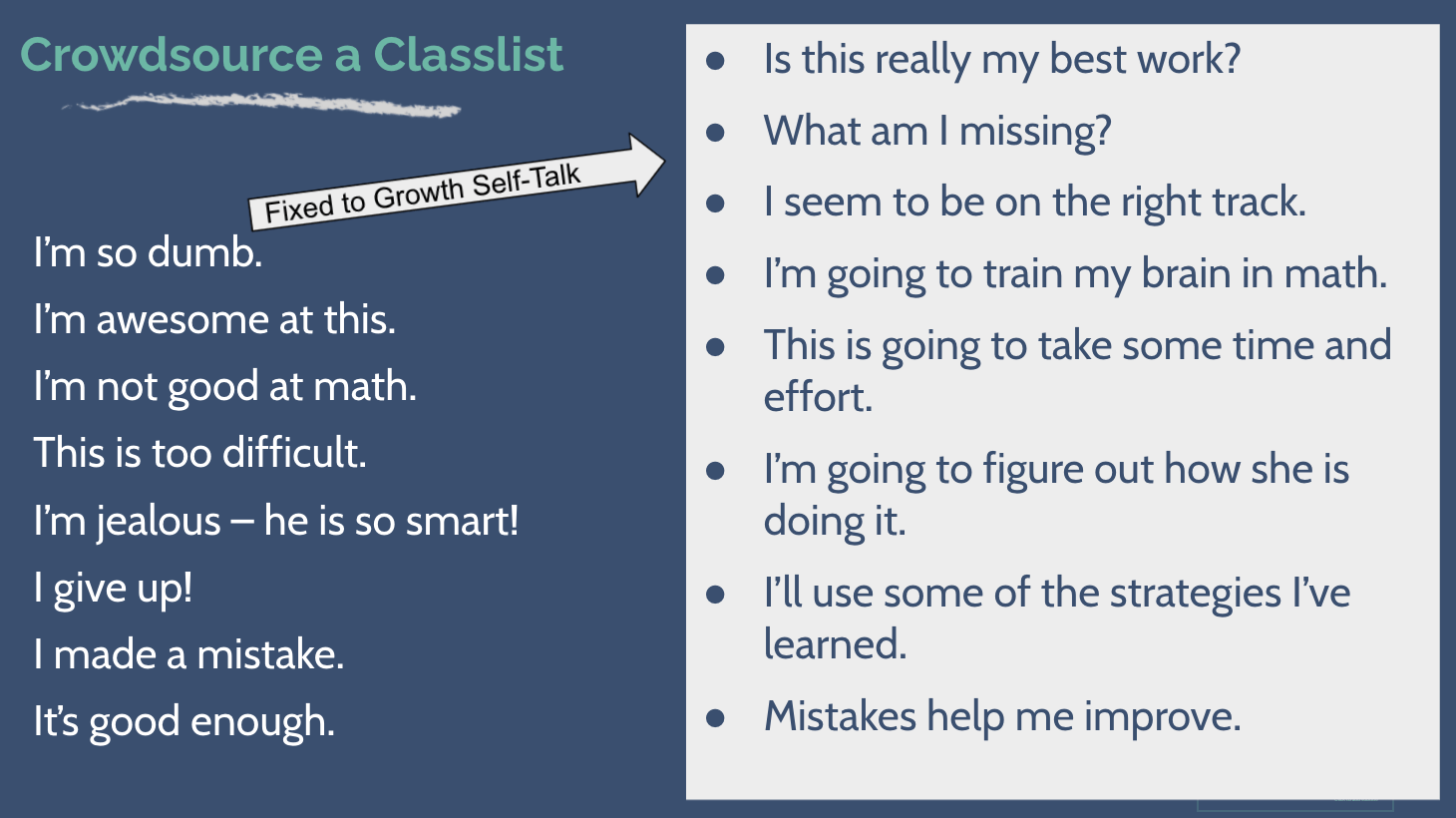

You could also generate a class list by collecting examples of nonproductive self-talk and brainstorm alternatives. See an example of this practice below. Classmates can then practice this with a trusted partner, or as trust and the culture grows this list can be posted for peers to support one another. When peer to peer language changes, the learning environment changes.

By creating a student culture of trust, respect and agency and consistently practicing growth mindset thinking, students will feel accepted in their learning community and will be ready to take on new learning challenges and encourage their learning community to do the same.

Rebecca MidlesRebecca Midles is the Vice President of Learning Design at Getting Smart and is an innovator in competency education and personalized learning with over twenty years of experience as teacher, administrator, board member, consultant and parent. Follow her on Twitter at @akrebecca.

Rashawn CaruthersRashawn “Shawnee” Caruthers is the Director of Learner Experience at Getting Smart and is a longtime educator with a background in marketing, journalism and advertising. She has a particular interest in CTE, words and empowering young people to control their own narrative.